Faculty pay attention

When I started teaching, I didn’t worry much about either my salary or student plagiarism. I figured that universities work on the honor system, and I’d rather let someone else fool me than make a fool of myself by becoming a classroom cop or fretting over a few dollars.

When I started teaching, I didn’t worry much about either my salary or student plagiarism. I figured that universities work on the honor system, and I’d rather let someone else fool me than make a fool of myself by becoming a classroom cop or fretting over a few dollars.

But being taken for a fool gets old pretty quick. I now do everything I can to prevent plagiarism. Unfortunately, the university funding crisis and dismal job market make it rather difficult to increase my salary. On good days, if I could afford it, I would do my job for free. On other days, it galls me to be underpaid.

Calling attention to low pay for full-time faculty doesn’t seem likely to win much public sympathy. Most people today get by on considerably less. Nonetheless, it’s worth getting the facts straight on faculty pay.

Yesterday the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) released its annual report on U.S. faculty salaries. Average full-time faculty pay increased 1.8 percent in the 2011-12 academic year, while inflation was about 3 percent. In fact, “2011-12 marks the third consecutive year—and the sixth year in the last eight—in which the change in average full-time faculty salary has fallen below the change in the cost of living.”

Use this interactive table to check out average faculty salaries at particular schools. And remember that disciplines with more perceived market value – business, economics, law, engineering, computer science – enjoy higher faculty salaries than the liberal arts. For example, according to the 2010-2011 AAUP faculty salary report, assistant professors in Business make more than double those in English (table H). The familiar explanation is that high private-sector salaries drive up faculty pay in these disciplines. It’s not because their faculty are more qualified, work longer hours, teach more effectively, or contribute more to society (some do, some don’t). It’s also not because their graduates get better jobs. Considerable evidence (here and here) suggests that liberal arts majors, while facing an initial disadvantage on the job market, eventually either match or surpass career-oriented majors in both salary and job satisfaction.

This means that faculty in some disciplines receive higher pay due to labor market dynamics that have nothing to do with the intellectual and vocational purposes of the university. And what makes sense from a market perspective can be disastrous from an organizational perspective. Large salary inequalities within a single campus undermine faculty morale and shared governance.

The AAUP report does not include salary information on contingent faculty, who teach most U.S. college courses and are paid far less than tenured and tenure-track faculty. The Coalition on the Academic Workforce (CAW) is preparing a report on the issue, due to be released this spring.

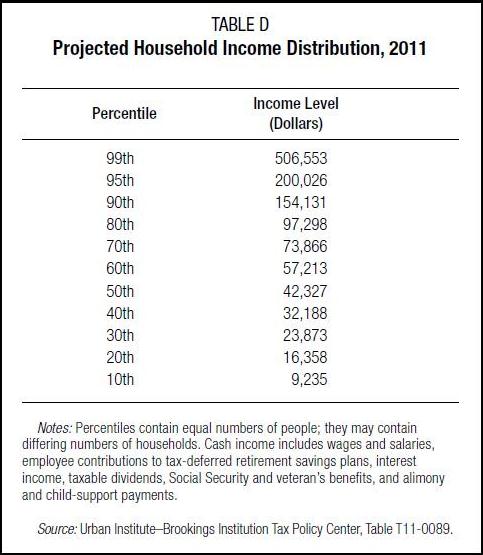

This year’s AAUP report discusses student tuition (rising), presidential compensation (excessive), and the impact of unions on faculty salaries (positive), and it concludes by considering faculty salary in the context of U.S. national income distribution and the Occupy Movement. Most full-time tenured and tenure-track faculty receive salaries higher than the bottom 50 percent and lower than the top 20 percent of U.S. households.

Are full-time faculty underpaid? Given our education, workload, responsibilities, and societal contribution — yes, many of us are terribly underpaid, especially when you consider our previous years of very low pay as research and teaching assistants. But rather than pondering exactly where faculty salaries belong on today’s scale of average household income, it seems more important to focus on the corrosive inequality reflected in the scale itself.

One cause of that inequality is the failure of many one-percenters to recognize what they get from the rest of us. The AAUP report notes that 94 of the 100 largest U.S. corporations have CEOs who are college graduates (36 from U.S. public institutions).

Entrepreneurs without college degrees, such as Rupert Murdoch, Steve Jobs, and Bill Gates, are the exceptions. Looked at from one perspective, the real job creators are the college professors who taught the occupants of the corner offices many of the skills they needed to ascend the corporate ladder, including those gained from courses in fields such as philosophy, English, and the fine arts.

So if you happen to know any one-percenters, tell them to check in on their former college professors now and then. There’s always more to learn.

Slacker U

It’s been two weeks since the Washington Post printed an opinion piece with the faux inquisitive title, “Do college professors work hard enough?” The widely criticized op-ed by David C. Levy, former chancellor of the New School University, argued that professors at teaching-focused universities don’t work very much, they’re grossly overpaid, and the two factors together are a major cause of the university funding crisis. Levy wrote:

An executive who works a 40-hour week for 50 weeks puts in a minimum of 2,000 hours yearly. But faculty members teaching 12 to 15 hours per week for 30 weeks spend only 360 to 450 hours per year in the classroom. Even in the unlikely event that they devote an equal amount of time to grading and class preparation [excuse me?], their workload is still only 36 to 45 percent of that of non-academic professionals. Yet they receive the same compensation.

As many bloggers pointed out (among others, here, here, and here), Mr. Levy’s article is incredibly ill-informed. University faculty obviously spend far less time in the classroom than preparing, grading, and advising, not to mention university service (committee meetings), community service, and research.

As one critic wrote, “Measuring faculty workload solely in terms of classroom time is like measuring athletes’ workload based on how long the event takes. By that measure, sprinters are the laziest people on earth — they work only seconds per day!”

Unfortunately, Levy’s ignorance about what academics do all day is fairly common – as anyone knows who has read the online reader comments when the local newspaper prints a story about university faculty.

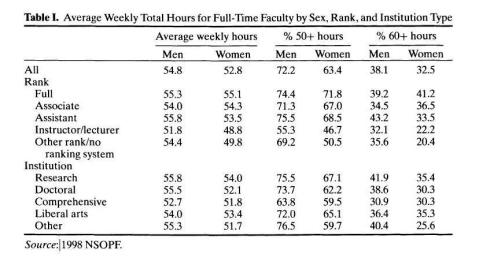

Facts alone won’t overcome popular assumptions of faculty sloth, but it’s worth mentioning a 2004 study (discussed here) by Jerry Jacobs, a sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania (using 1998 data from a national cross-section of four-year public and private nonprofit institutions). The study found that full-time faculty at U.S. universities worked an average of over 50 hours per week (men: 54.8 hours/week, women: 52.8 hours/week). By comparison, men in the U.S. labor force worked an average of 43.1 hours per week, and women 37.1 hours per week (outside the home). Male professionals and managers worked 46.0 hours per week, and female professionals and managers an average of 39.5 hours per week. That means university faculty worked between 8.8 hours (men) and 13.3 hours (women) more hours per week than managers and professionals.

It’s also crucial to remember that adjunct faculty actually teach the majority of U.S. college courses, usually in exchange for terrible pay and low job security. As Laurie Essig points out, “According to an AFT survey of teaching positions from 1997-2007, ‘contingent faculty’ rose from 2/3rds of all positions to 3/4ths. In other words, only about 25% of faculty are tenured or tenure-track.”

In response to the op-ed, Lee Bessette called for a “Day of HigherEd” on which faculty would “record, in minutia, what we do as professors from the moment we wake up to the minute we fall asleep.” Read about faculty days here, here, and here. And read about a university staff person’s day here, and the day of a community college dean here. Here’s a wrap of the exercise. I get exhausted just reading them.

As Chris Newfield wrote:

These descriptions of everyday faculty life describe an industry which is structurally understaffed. It describes a professoriat whose creativity is under continuous pressure and where invention in fact requires exceptional effort. This is at bottom a management problem, [but] for at least a generation management has defined productivity entirely through the cutting of labor costs: working conditions and hence work output, that is, research and learning, have during my career never been seriously discussed.

Despite all this, most faculty love their jobs – which makes us even more frustrated that we increasingly lack the conditions necessary to do our jobs well.

Many other workers are also frustrated, of course, especially those who have no work at all. Whatever your situation, it’s rarely difficult to find someone else who is worse off. University faculty enjoy flexible schedules and creative opportunities that most workers lack. But those features of our profession are eroding, as are the conditions under which they benefit not only faculty but also our students and the general public.

Food research and institutional corruption

The cheerful labels call out as I walk through the supermarket: Quaker Oats “can help reduce cholesterol,” Green Giant veggies “may reduce the risk of heart disease,” and Hershey’s chocolate has “antioxidants,” which I’ve heard are good for you. And do you remember Jamie Lee Curtis teaching us that Activia yoghurt is “clinically proven to help regulate your digestive system in two weeks”? Saturday Night Live did a hilarious sketch about Activia, but I suppose those in need might have concluded the yoghurt works even better than promised.

The cheerful labels call out as I walk through the supermarket: Quaker Oats “can help reduce cholesterol,” Green Giant veggies “may reduce the risk of heart disease,” and Hershey’s chocolate has “antioxidants,” which I’ve heard are good for you. And do you remember Jamie Lee Curtis teaching us that Activia yoghurt is “clinically proven to help regulate your digestive system in two weeks”? Saturday Night Live did a hilarious sketch about Activia, but I suppose those in need might have concluded the yoghurt works even better than promised.

A couple days ago I participated in a fascinating workshop at Penn State on “Industry Sponsorship and Health-Related Food Research,” sponsored by the Rock Ethics Institute at Penn State and the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics at Harvard. It was part of a long-term Safra Center project on institutional corruption.

Institutional corruption goes beyond bribery and other individual illegal acts. It involves ongoing practices, often entirely legal, which undermine the purpose, integrity, or public trust of an institution.

The workshop focused on “functional foods,” which the U.S. Institute of Medicine defines as “any food or food ingredient that may provide a health benefit beyond the traditional nutrients it contains.”

Healers of both respectable and dubious qualification have long touted the medicinal properties of various foods, but U.S. regulatory law used to distinguish fairly clearly between food and drugs. The Nutritional Labeling and Education Act of 1990 blurred this distinction by allowing food labels to include FDA-approved health claims, which must be supported by “significant scientific agreement.”

Scientific agreement is often lacking, so food companies often resort to qualified health claims (“some evidence suggests . . . may reduce risk of”), and increasingly they rely on vague “structure-function” claims (“calcium builds strong bones”), or nutrient content claims (“Omega-3 eggs”). These last two kinds of claims avoid depressing talk of disease, and they don’t burden consumers with wordy qualifications. They also don’t require FDA notification or approval. Producers must provide scientific evidence upon request, but so far the FDA has issued only two warning letters about structure-function claims. The European Union, in contrast, requires prior government approval for any health or nutrition claim in food marketing.

University-industry partnerships play a big role in research on functional foods. Press releases simplify the research conclusions, and the media produce sensationalized coverage of the latest wonder food. Evidence suggests that industry-funded studies tend to reach conclusions favorable to industry. That doesn’t mean the conclusions are always wrong, but the research requires more careful public scrutiny.

Moreover, the problem is not only biased evaluation of evidence, but the type of questions that researchers ask in the first place. Most research on functional foods examines only potential benefits, neglecting potential risks. If people substitute a functional food (“antioxidant chocolate”) for other food or behavior (exercise), they may end up worse off than before. Dannon claimed that Activia promotes “regularity,” but the company didn’t mention that the yoghurt does so only if you eat at least three containers per day. (In an unusual move, the Federal Trade Commission charged Dannon with deceptive advertising, and the company agreed to pay $21 million and to stop making such health claims without FDA approval.)

What to do? Improved conflict-of-interest guidelines may help. Food research is increasingly global, and the Singapore Statement on Research Integrity suggests a set of global standards. But such guidelines and standards remain empty gestures if they aren’t supported by institutional changes. Possible institutional measures include research programs on potential negative effects of functional foods, a certification system for independent public-interest food scientists, and improved government regulation of functional food claims.

More broadly, I wonder how to promote research and education on functional foods without succumbing to the common image of food as technology. I once heard a French chef say that after dinner American parents ask their kids if they got enough to eat, whereas French parents ask how the food tasted. Despite their promise, we shouldn’t let functional foods obscure the cultural and aesthetic dimensions of what and how we eat.

Guten Appetit!

Report on “for-profitization” of CSU

Last week the California Faculty Association (CFA), the CSU’s state-wide faculty union, released an important report on the commercialization of higher education: “For-Profit Higher Education & the CSU: A Cautionary Tale.”

Under the guise of increasing student access, the report persuasively argues, the CSU trustees have been adopting policies that echo the approach of private, for-profit universities.

For-profit universities have been getting a lot of publicity — the P.T. Barnum kind. Driven by unmet public demand and slick marketing, they’ve been growing like weeds: in 1990 about 1 percent of American college students were enrolled in for-profits; today it’s 12 percent. Studies of for-profits have repeatedly found exorbitant executive pay, precarious faculty employment conditions, high student tuition and student debt, low graduation rates, and low post-graduation student employment rates. And that’s not to mention the executive fraud and two-bit pedagogy.

Maybe not the best model for the CSU.

But as the CFA report documents, for-profit thinking is spreading throughout the CSU. You might consider this a major public issue.

Unfortunately, that issue is not being debated – in fact, the question is not even being asked – because what might be described as a process of “for-profitization” of the CSU is taking place quietly, with virtually no accountability for system leaders, with limited faculty and staff participation, and with no involvement of the public or elected officials.

The CFA report examines “for-profitization” in four areas:

Executive compensation. As you’ve probably heard, both CSU faculty salaries and the number of permanent faculty positions have stagnated, despite student enrollment growth of 18 percent over the past decade. But campus presidents have been struggling through these tough times fairly well, enjoying a 71 percent salary increase during the same period. As Sacramento State history professor Joseph A. Palermo asks, “Why should these people be paid more than the Governor of California, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and even the President of the United States?”

Of course, reducing top executive salaries is not by itself going to solve the CSU funding crisis, and some may say the issue is merely symbolic. But symbols reflect and reinforce attitudes, and attitudes lead to policies.

Student fees. In the past, when love of learning didn’t motivate my students to finish the assigned reading, I would sometimes tell them to consider their obligation to the California taxpayers who were paying for most of their education. That argument isn’t going to fly anymore: Over the past ten years, the report states, student fees have gone up 318 percent, and last year, seven CSU campuses got more money from student fees and tuition than from the State.

Extended Education. One of the CSU administration’s ideas for responding to the budget crisis is to expand Extended Education (also known as Continuing Education), which was long the preserve of a modest number of mid-career “non-traditional” students. Unlike regular student fee increases, tuition increases for Extended Education are not subject to California public notice and comment requirements. So it’s not surprising that undergraduate tuition for Extended Education in 2010 was 51 percent higher than average fees for the regular CSU, and in some cases it was double.

The target population for the administration’s planned expansion of Extended Education includes, of course, the most appropriate groups: students who need remedial courses, students who postpone their studies for a term or more, students who require high-demand “bottleneck” courses, and students who have not completed their degrees within five years. Nice to see the CSU planning to help out these students with more expensive courses.

There are currently various legal barriers to a radical expansion of Extended Education, but:

In the coming years, if the administration and Trustees succeed in overcoming these barriers, more and more matriculated students may find themselves paying both higher tuition to attend the public university and a bounty to Extended Education in order to get the classes they need to graduate.

Online education. The CFA report notes that online education potentially offers increased access for some students. But the new initiative called Cal State Online raises serious concerns about quality and cost that need to be more thoroughly and publicly addressed, especially since studies suggest that “quality online education is NOT cheaper than more traditional modes of instruction.”

The report concludes with a call to:

- Democratize the CSU Board of Trustees by including more voices and improving public access to its meetings.

- Control the salaries of top CSU executives to make them similar to the salaries of other public servants.

- Improve student access by increasing public funding and lowering fees, rather than by reducing quality.

Sounds like a plan to me. But the developments described in this report have been gathering momentum for a long time, and they’re happening throughout higher education. Serious improvements will depend on the “strong and slow boring of hard boards.”

Commerical sign update

If you’re at Sacramento State and you walked into Tahoe Hall during the past couple days, you might have noticed that the new digital signs were no longer showing commercial videos — in fact, the video monitors were off for over a week, but today they went back on.

They weren’t shut down by a power outage, natural disaster, or hack attack. And it wasn’t the fearsome public scrutiny generated by my previous posts. From what I’ve been told, the signs were off because the Executive Committee of the Faculty Senate asked the Vice President for Advancement to look into the matter, and the VP asked the Business School to stop broadcasting videos that violate the campus digital sign policy, which bans commercial messages.

Now the digital signs are back on, and the videos I saw were advertising the Business School’s MBA program. That’s an improvement over the previous videos, most of which were corporate recruitment ads that sing the praises of working at Target, SMUD, Wells Fargo, and other companies, presumably the same companies that donate to the Business School. Of course, Sacramento State has a thriving Career Center that provides far more complete and impartial advice than students can get while walking past these videos on the way to class.

The digital stock tickers have been on the entire time, and they’re still on, even though they also violate the policy. Many stock tickers, including the famous one at Times Square, show only stock prices and traditional ticker symbols that consist of a few letters. Our stock tickers display a cheerful parade of bright corporate logos. To my mind, that violates the campus ban on showing commercial messages on digital signs.

Is any of this worth worrying about? How slippery is the slope?

Consider that just down the road at UC Davis, which apparently bans most commercial advertising on campus, a local advertising agency recently started “covering lecture halls with flyers and promoting discounts on pizza through 4 inch by 6 inch cards taped to seat backs.” The editors of The California Aggie say this is “devaluing the sacred nature of these areas,” and they half-jokingly suggest the next step is “product placement being laced into discussions about metaphysics.”

Or watch this short New York Times video, which shows how corporations have started hiring “student brand ambassadors” — about 10,000 American college students last fall — to promote their products on and off campus. Not content with marketing to students, businesses are now “marketing through students.” Last August Target hosted a welcome party for first-year students at the University of North Carolina. Students wearing identical t-shirts from American Eagle helped new arrivals move into the dorms, while handing out company coupons and goodies. The students in the video don’t seem to have many concerns about either coercion or corruption. But as one UNC administrator said about the Target event, with heroic understatement, “It’s a bit of a dilemma.”

Coercion and Corruption

A couple years ago I wrote an essay on “coercion” and “corruption” as two basic objections to the commercialization of academic research. It was published in an edited volume. I adopted the distinction between coercion and corruption from a paper by the political theorist Michael Sandel, “What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets” (Sandel has a book of the same title coming out soon.) Here’s the basic argument, with a few thoughts on how it applies to university politics:

Coercion occurs when economic inequality forces people to buy or sell things they otherwise wouldn’t. Those with more money can shape agendas and outcomes to their advantage. Those with less money may do things out of economic need rather than voluntary choice. That’s one reason most countries ban or regulate payment for sex, surrogate pregnancy, and human body parts, among other things. People who accept money in exchange for these things often do so out of necessity, and in that sense, they are coerced.

Coercion arguments show how collaborations between universities and businesses often create unequal power relations within the university. When some colleges and departments – usually business, engineering, applied sciences – have close ties to major corporations, they easily acquire more influence on campus than others. Other departments may be forced to accept conditions and policies they otherwise wouldn’t. More generally, many public universities today are subject to coercion, because the decline in public funding creates economic pressure to find money elsewhere. Corporations are happy to oblige, usually with subtle or not-so-subtle strings attached.

A key limitation of coercion arguments is that they have little to say when fair bargaining conditions allow people to freely sell things that others think should never be sold. For many people, a regulated market in sexual services or human kidneys — complete with measures to ensure informed consent and equal access — would still be morally wrong. Or consider scientists with generous public funding, who freely design research projects to maximize their commercial potential (as many increasingly do) — something may still be wrong, despite the absence of coercion. That’s where the corruption argument comes in.

Corruption results from morally or culturally inappropriate exchanges of goods and services. Society can be understood in terms of different spheres of activity – politics, commerce, science, education, art, and so on – and justice depends on provisional boundaries between them. Money is the most common threat to such boundaries, because money can be exchanged for so many things. Most people agree that it’s wrong to buy a baby, sell a term paper, or judge art by its market price. But money is not the only source of inappropriate exchanges: it’s also wrong to trade a baby for a car, or raise a student’s grade in exchange for mowing the lawn.

None of this means that money is evil or that it shouldn’t play a role in education, politics, or art. After all, someone has to pay the bills. University faculty need to be paid an appropriate salary, but their research and teaching should be evaluated according to professional standards, not personal preferences or commercial potential. In this sense, faculty are paid to do research and teaching; they are not paid for research and teaching.

As I wrote before, our campus policy on digital signs includes a ban on commercial messages. Why? It’s probably not because people feel coerced by such messages. A stock ticker that displays corporate logos doesn’t force anyone to buy products or stock from those corporations. And broadcasting corporate recruitment ads doesn’t force anyone to apply for a particular job. But commercial messages corrupt the learning and research environment of the university. They ask people to consider what’s worth buying rather than what’s worth knowing. Universities require a commitment to fair and open inquiry, which is threatened when those in charge seem to be promoting particular economic or political interests.

A key difficulty with corruption arguments is that people don’t always agree on what counts as corruption. Some people think prostitution is fine as long as it’s safe and voluntary, others do not. Some people are bothered by corporate logos on university buildings, others are not.

Coping with such disagreements isn’t easy, because they involve conflicts over the basic meaning and purpose of the activities in question. But that’s why we have institutions and practices of self-government. In universities these include various committees and councils and the faculty senate. They’re never perfect, but we could probably make better use of them.

Why get involved?

Students often tell me they would like to get involved in politics of some kind, but they worry that they won’t have any impact and will waste their time. Like everyone else, they don’t want to be duped into thinking they can change something, if they actually can’t. And they especially don’t want to look like fools or be accused of tilting at windmills.

A good response to such worries (and it’s not only students who have them) is to consider why a person should get involved in politics in the first place. What are the purposes and outcomes of political engagement? We hear a lot of praise for people who “make a difference.” There’s even a regular NBC News segment devoted to assorted difference makers. How influential are they? Sometimes it’s hard to say, and scholars disagree about the relationship between political activism, institutional structures, and social change. In some contexts, the initiative for change may come from policy makers and other elites, rather than from grassroots activists. Sometimes disruptive protest tactics are effective, other times a moderate approach works better, and sometimes they complement each other. But overall it’s clear that political engagement matters enormously. Ordinary people working together have “made a difference” at all levels of government; they’ve brought about changes large and small in businesses, schools, universities, and other associations; and they’ve shaped economic conditions, political opportunities, and cultural practices of all kinds. Citizen activism has also played a key role in many major social reforms that we now take for granted, including universal suffrage, workplace safety, anti-discrimination law, environmental protection, and so on.

Nonetheless, focusing on outcomes can easily become paralyzing. Goals are often distant and success unlikely. Making things different doesn’t always make them better, and you can never be sure where your actions might lead. Politics is unpredictable.

So it’s worth remembering that making a difference for others is only one possible outcome of getting involved in politics. You might also make a difference for yourself — or in yourself. It can be personally enriching to speak publicly about something that really matters to you, regardless of what happens next. Political engagement can strengthen friendships, build community, and educate yourself and others. (And it can destroy friendships, alienate colleagues, and be incredibly frustrating for yourself and others — but hey, as my dad says, it’s an imperfect world.)

Now, the trick is that these personal benefits of speaking in public are byproducts of trying to make a difference. If personal enrichment is your main goal, then speaking in public won’t do much for you. Better just go back to piano lessons. If you try to enrich yourself by speaking out, you’ll become narcissistic and self-involved, and your actions won’t enrich you or anybody else.

Think of falling asleep: the harder you try, the less likely you’ll succeed. The same goes for self-confidence, self-respect, spontaneity, falling in love, and even smiling. (Here’s a test to see whether you can spot a fake smile.) The social theorist Jon Elster calls such things “essential byproducts,” because you can only get them indirectly, as a byproduct of doing something else.

The same principle applies to competitive sports. You may value the companionship and health benefits they bring, and maybe in some sense “everybody wins,” but if you don’t try to win you’ll ruin the game.

When it comes to political engagement, even though your actions may have little prospect of success, you need to try to succeed, or else you’re just messing around. But if you don’t succeed, there’s a good chance you’ll still get something out of it.

Having said that, everyone needs to find a way to get involved that’s right for them. Don’t like giving speeches? Attend a demonstration and carry a sign. Don’t like sleeping in a tent? Write letters to the editor of your local paper. Don’t like any of the political clubs on offer? Start one with some friends.

In any case, do your best to make a difference, but don’t assume your effort will have been wasted if you don’t.

Campus sign policy: No commercial messages

Established policies are rarely perfect, but they do allow people to avoid reinventing the wheel every time a new controversy arises. I recently discovered that Sacramento State has established Digital Signs Guidelines and Policies. The policies distinguish between “internal” and “external” digital signs, and I suppose people might disagree about whether the new digital signs in Tahoe Hall should be considered internal or external. They are in a covered breezeway, doors on one side, open to the elements on the other. But the differences in the policies for internal and external signs don’t seem relevant here. (It also seems that these signs are not part of the “SacConnect” campus digital sign network, but the policy apparently applies to all digital signs on campus.) Here are some key passages:

CORE REQUIRMENTS OF ALL CAMPUS DIGITAL SIGNAGE:

The digital signs on campus will provide the campus community with:

- Emergency messaging

- Information about campus events, activities and services.

The new digital signs in Tahoe Hall are broadcasting “corporate messages,” and so they apparently do not meet these Core Requirements.

Approval process for external signage messages

Public Affairs will review and approve or deny all exterior digital sign purchase, placement and message requests. Decisions should be made on the basis of compliance with the core requirements of campus electronic signage and content submission policy. The understanding is that messages should be limited to avoid digital “pollution.” All Public Affairs decisions are final.

This sounds like the Public Affairs office would need to approve the new signs in Tahoe Hall. I don’t know whether it did. The website does not specify a separate approval process for internal signs.

Most importantly, the content policy for both internal and external digital signs clearly states:

No commercial or other for-profit messages.

As I mentioned before, Dean Varshney said that the videos in question are “corporate messages” and not commercial messages. I’ve stood there and watched the videos (a good way to harvest strange looks from students), and I think many of them are definitely commercial messages. In any case, it seems clear that the new digital signs in Tahoe Hall violate the spirit, and probably the letter, of the campus policy on digital signs.

Fundraising ethics

Like most universities these days, Sacramento States raises a lot of money from private donors. Such donations bring significant benefits, but they also raise difficult questions about whether and how donors might influence the university’s core activities of teaching and research — either directly, or more likely, indirectly.

The section on Fundraising Ethics in Sacramento State’s Development Policy Manual states:

All philanthropic activities at California State University, Sacramento will follow the ethical standards and guidelines promulgated by the Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE) and the Association of Fundraising Professionals (AFP), and particularly the Donor Bill of Rights.

The CASE Donor Bill of Rights specifies ten rights of philanthropic donors that aim, “To assure that philanthropy merits the respect and trust of the general public, and that donors and prospective donors can have full confidence in the not-for-profit organizations and causes they are asked to support.” For example, donors have a right:

To be informed of the organization’s mission, of the way the organization intends to use donated resources, and of its capacity to use donations effectively for their intended purposes.

To be assured their gifts will be used for the purposes for which they were given.

To receive appropriate acknowledgment and recognition.

This statement of rights raises some questions about the new video monitors in Tahoe Hall that I wrote about a couple days ago. As I said, my understanding is that the Business School is not receiving any direct payment for broadcasting corporate messages on these monitors. Dean Varshney explained to me that the Business School broadcasts these videos as a gesture of good will toward selected donors. They express appreciation for an ongoing relationship. But then it’s worth asking:

- What are the “intended purposes” of corporate donations to the Business School?

- Have the donors been assured that their gifts are being “used for the purposes for which they were given”?

- Is the acknowledgment of these gifts with the continuous broadcasting of corporate video messages in a public space “appropriate”?

- Do such video messages risk damaging the “respect and trust of the general public”?

We can’t answer the first two questions without more information from the Business School and its donors. But if “appropriate” means conducive to the university’s mission, then acknowledging corporate donations with commercial messages is definitely not appropriate in the sense intended by the Donor Bill of Rights, which is endorsed by Sacramento State’s Development Policy Manual. And assuming that the general public expects a Business School to teach about brand loyalty and not teach loyalty to brands, then the new digital signs in Tahoe Hall do not promote the public’s “respect and trust.”

Commercialization up close and personal

At first glance this post is about a minor issue. The elusive Real Problem lies elsewhere. But sometimes small events are part of a pattern. Think of racist or sexist jokes, which disturb not merely because they offend, but because they are linked to larger inequities.

At Sacramento State the Business School occupies the first two floors of Tahoe Hall, and on the third floor you can find the departments of government, economics, history, and public policy, as well as the Center for California Studies. Back in October I arrived on campus one day and saw that someone had installed two digital stock market tickers in the entry areas of the building, where hundreds of people walk past everyday on their way to classrooms and offices. Many third floor faculty were angry. The issue was raised at a faculty council meeting of the College of Social Sciences and Interdisciplinary Studies (SSIS), and we requested a meeting with the Dean of the Business School. Scheduling difficulties ensued. Then one day in early February we were surprised to find large video screens below the stock tickers, continuously broadcasting commercials for Wells Fargo and AT&T.

On March 6 several third floor faculty, plus the deans of SSIS and Arts & Letters, finally met with Business Dean Sanjay Varshney. (You may remember Dean Varshney from his controversial study on California’s global warming legislation.) Third floor faculty politely explained their view that all faculty whose offices and classes are in Tahoe Hall should be represented in decisions on major changes to public areas. Department chairs could have suggested reasonable modifications to the installations, but they were not consulted.

Third floor faculty also expressed substantive concerns: playing selected “corporate messages” (as Dean Varshney called them) may lead students to ask whether faculty are biased toward those corporations; faculty should be teaching about brand loyalty, not teaching loyalty to brands; the video monitors and stock market tickers project a business-friendly sensibility that undermines our efforts to help students analyze business activities in an objective manner.

In response Dean Varshney said that for years others had neglected the public appearance of Tahoe Hall, and now that he had finally made it look nice, people were complaining. (The Business School has also installed various other amenities, like plants and directional signs, which I don’t think anybody minds.) He said the video screens are no more objectionable than putting a donor’s name on an academic building. The Business School, he explained, needs to project a clear identity, meet student expectations, and attract corporate donors. He said that involving the third floor departments in decisions on how to use the public areas would inevitably take too long and fail to produce any agreements.

A couple days later I stopped by Dean Varshney’s office to ask a few more questions. Contrary to what some of us thought, he said the Business School does not receive any direct revenue for showing the video messages. About one-third of the Business School’s budget comes from private donors, and Dean Varshney sees the video messages as a good will gesture that helps maintain positive relations with these donors.

Dean Varshney repeatedly stressed his good intentions, and I see no need to question them. But his actions suggest that, on this issue so far at least, he is doing more to maintain positive relations with corporate donors than with his colleagues in Tahoe Hall.

Dean Varshney also explained that the video messages will help increase the visibility of certain employers for Business School graduates. In the future, he said, some of the videos will showcase student activities, but he couldn’t say how many. When I asked whether other departments could show their own videos, he said the Business School would expect payment in return. By way of comparison, a few years ago the university installed a giant digital sign by Highway 50. It’s owned and operated by Clear Channel, but some of the revenue is shared across campus, and one out of every eight ads is for something at Sacramento State.

Dean Varshney has been courteous and generous with his time, and I’ve tried to present his arguments fairly. If you’re familiar with the culture of business schools, these installations probably seem like no big deal.

But our Business School is not out in a field somewhere. It is part of this (for now) public university. If the Business School receives one-third of its funding from private donors, then I suppose it receives about two-thirds from students and taxpayers. The university needs to maintain a built environment conducive to its mission, which does not include preferential assistance to the publicity efforts of selected corporations.

The award-winning film “Inside Job” showed how top business schools provided academic legitimacy for policies that contributed to the financial meltdown of 2008 (here’s a relevant clip), and now business schools are being scrutinized for conflicts of interest. They should probably avoid doing anything that creates even the appearance of such conflicts.

Our department can’t afford fancy video screens, but we’re looking into putting up some messages of our own. Please post your suggestions, or any other responses, in the comments section.

![By Victor Dubreuil (private collection) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://i0.wp.com/upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6b/Victor_Dubreuil_-_Barrels_on_Money%2C_c._1897_oil_on_canvas.jpg)